Even before the pandemic, youth unemployment in the European Union was three times higher than among the over-55s. COVID-19 threatens to undo the last decade of progress: policymakers must act to avoid Europe’s youth suffering the scarring effect.

Youth unemployment increased dramatically in several European Union countries during the Global Financial Crisis. It took several years before youth unemployment rates came down to, or fell below, pre-crisis levels. Even by 2019, this had not been achieved in all EU countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic is now posing the same threat: younger generations are facing a harsher labour market than older generations.

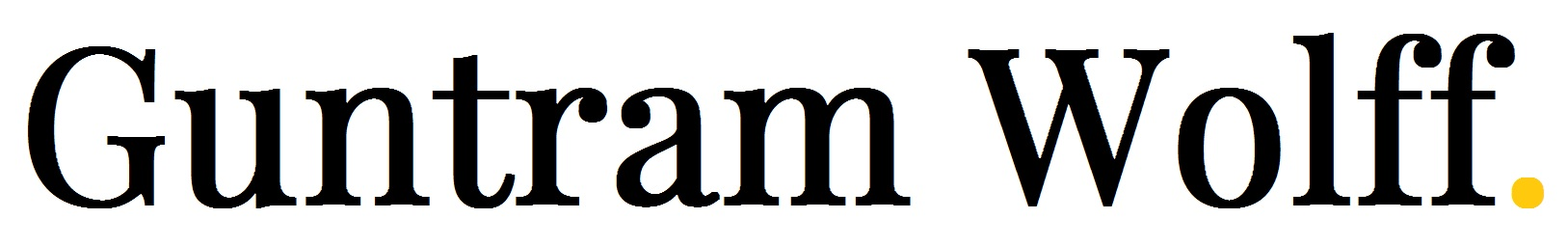

Fig. 1 EU Unemployment rates (%labour force)

source: Bruegel based on Eurostat

Figure 1 shows unemployment in EU countries for workers aged 15-24 and those aged 55-64. Youth unemployment increased during the second quarter of 2020, while unemployment remained almost unchanged compare to the year before for the older cohort (we did not find a significant difference when adjusting youth unemployment for gender; see Fig. 2 in the annex).

A glance at labour market slack data, or the shortfall between the work desired by workers and the volume of work available, does not provide any cause for optimism.

[infogram id=”1pql0mepwjkepnfq7p395e0dw9f0vk3dq66″]

Table 1 shows that young active jobseekers are two or three times less likely than those aged over 55 to be able to find a job. The professional experience of older people plays a crucial role in this disparity, which makes tackling unemployment among young people all the more pressing in times of rising unemployment.

Moreover, Table 2 shows a substantial increase in the proportion of under-25s who are not even seeking work, even though they are available to work (unemployment figures only include those who are actively seeking work: the numbers in Table 2 include discouraged jobseekers and persons prevented from looking for work due to personal or family circumstances).

The scars left by youth unemployment

Youth unemployment should worry policymakers.? Beyond the immediate negative effects of unemployment on individuals and public finances, youth unemployment has been shown to have longer-term effects. The literature on the ‘scarring effect’, the effect of being young and unemployed, shows there are irreversible consequences (see for example Arulampalam, 2001; Darvas and Wolff 2016). For instance, Gianni De Fraja and Sara Lemos found that “an additional month of unemployment between ages 18 and 20 permanently lowers earnings by around 1.2% per year”. Burgess (2003) found that unemployment early in an individual’s career increases the probability of subsequent unemployment.

There is some controversy about the long-term effects of youth unemployment on the employment rate. Barslund and Gros (2017) and Mroz and Savage (2006) suggested limited effects, while Eurofound (2018) data showed higher long-term unemployment numbers. Eurofound (2017) data and Scarpetta et al (2010) highlighted longer-lasting scarring effects from long-term unemployment, including decreasing optimism about the future.

Schwandt (2019) showed that people who enter the labour market during a recession earn less and work more but receive less welfare support. Moreover, they are more likely to divorce, and they experience higher rates of childlessness. Furthermore, Strandh et al (2014) found that youth unemployment is significantly connected with poorer mental health. It is important to underline that periods of unemployment later in life do not appear to have the same long-term negative effects.

In summary, the labour market is much more difficult for younger people than older people. Like the last big recession, the economic fallout from the pandemic will leave many young people in Europe unemployed, with long-lasting social and economic consequences. Yet in the EU, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen did not identify youth unemployment as a key policy concern in her state of the union address on 16 September 2020. The European Commission and national policymakers must urgently focus on supporting young people in coping with the challenging situation. Beyond supportive macroeconomic policies, they must target funding towards the hiring of young people and training measures.

ANNEX

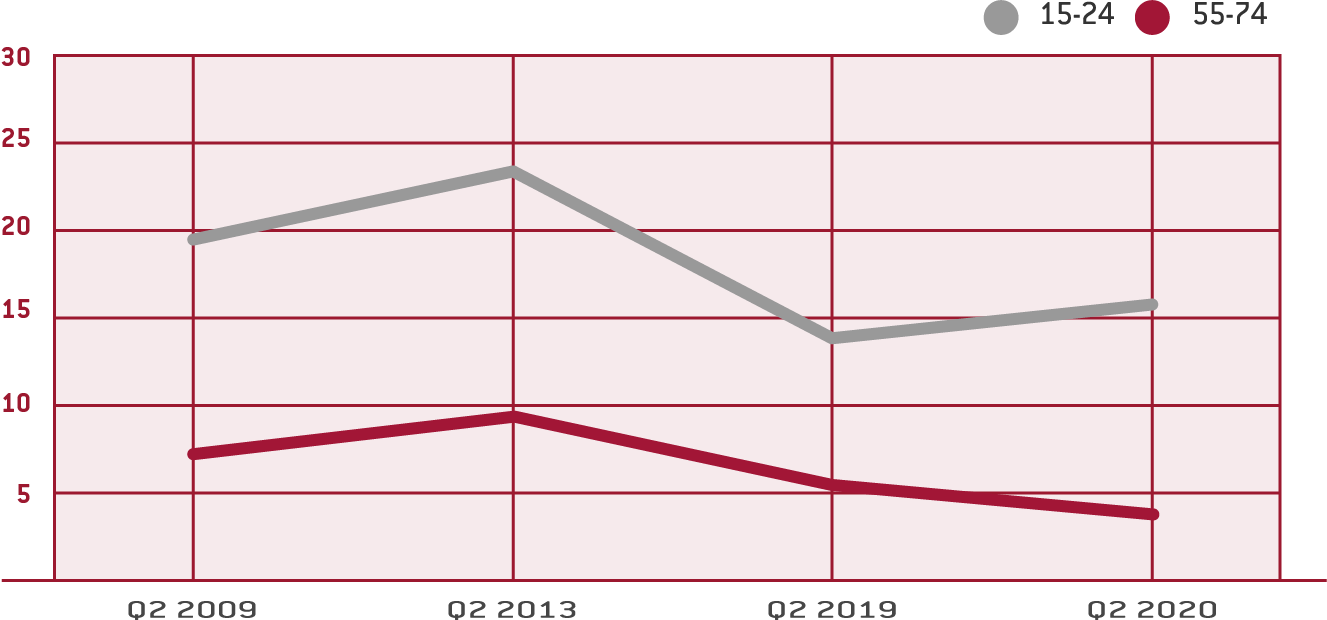

fig. 2: Youth employment by gender (19-24, % labour force)

This blog was produced within the project “Future of Work and Inclusive Growth in Europe“, with the financial support of the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.

Recommended citation:

Grzegorczyk, M. and G. Wolff (2020) ‘The scarring effect of COVID-19: youth unemployment in Europe’, Bruegel Blog, 28 November