European Union debt can provide comprehensive insurance against the COVID-19 pandemic and can enable a macroeconomic response, even though EU debt is a liability for taxpayers in EU countries and therefore indirectly for national budgets. To establish it, countries will need to give up control over some spending and some revenues. To be politically sustainable, that control should not be intergovernmental but be grounded in EU institutions. The EU Treaty offers some possibilities, but treaty change might ultimately be necessary. Democratic legitimacy is at the core of the debate.

The idea of a European COVID-19 pandemic recovery fund (to be discussed by EU heads of state on 23 April) has triggered a heated debate on joint borrowing. This blog post clarifies some of the concepts at the heart of this debate, concluding that EU debt to cope with the consequences of this crisis would tremendously increase the stability of the euro area. EU debt for the temporary catastrophic shock would provide effective insurance but multiple issues need to be solved. EU leaders should agree on multiple European Council meetings to solve them.

Why is joint borrowing desirable?

The magnitude of the current shock means that the economy needs huge public support. If the euro area only relies on national borrowing, backed by European Central Bank purchases, the debt of some countries might be considered unsustainable by markets, leading to a rise in spreads, which would then render debt unsustainable in a self-fulfilling crisis.

To anticipate and prevent such market movements, some countries might borrow too little, supporting their economies insufficiently. This could do long-term damage to economic performance and could drive the EU apart politically. Moreover, different levels of state-aid support for companies in different EU countries would undermine the single market.

Providing insurance against catastrophic shocks increases the stability of the system. And the stability of the system is in the interest of all members of the system. EU debt is highly desirable and necessary to preserve the integrity of the single market.

Is European debt a liability for national budgets?

Several commentators have argued that European debt would not be a liability at the national level. But is this really true? The answer is, unfortunately, no.

Any debt can only be incurred against a future stream of revenue that will pay the interest on the debt. The question is where this revenue stream will come from. One option is to use EU budget revenues. Those revenues, however, come from national budgets. Strictly speaking, EU debt would therefore represent a liability for all national budgets, and corresponding national budgetary resources would have to be committed to servicing that debt.

To avoid EU debt becoming a national liability, Garicano and Verhofstadt have proposed EU taxes, for example on big polluters and tax evaders. It is appropriate and logically consistent to finance EU debt through an EU tax. However, we should be clear that such an EU tax on polluters would mean that the revenues from such a tax would not accrue to national budgets. Previous EU taxes, such as tariffs, flow into the EU budget and thus reduce the need to draw on national budgets to finance EU expenses. In that sense, even an EU tax would mean an indirect liability for national budgets.

A special situation arises if a specific economic activity can only be taxed effectively at EU level. To avoid aggressive tax planning or even tax avoidance, some forms of capital income might need to be taxed at EU level and this revenue could be used for EU borrowing (Landais, Saez and Zucman). But again, the revenue raised would be used for debt and not to reduce national contributions to the EU budget.

In national accounting, ‘general government’ includes the central government, state governments, local governments and social security systems. As a meaningful EU-level government/debt is added, such EU debt would have to be added to the ‘general government’ account. Put differently, the tax base cannot be increased by adding an EU level.

But surely grants to countries should be preferred to loans?

Grants are a transfer of resources without a corresponding increase in a financial liability. One big advantage of EU debt is that one can separate the tax base from the spending decision. In other words, one could create a European debt based on a tax on polluters, borrow money on the markets and distribute it in the form of grants to those parts of the EU that most need funds. Economically, this would mean inter-regional transfers, which would be very helpful in dealing with the current shock. Politically, this is one of the main reasons why EU debt is so controversial. The EU is able to provide some inter-country transfers through the EU budget, but transfers, even within countries and political unions, are very controversial.

Does joint borrowing require joint spending?

Typically, in federations, joint or central borrowing is combined with central control over spending. Let’s take the example of the Federal Republic of Germany. It is unconceivable that a German federal finance minister would borrow and give the proceeds to the Bavarian prime minister to spend without any oversight or control. German federal borrowing is used for federal programmes, even though states administer large parts of the programmes.

One of the most important questions is therefore what kind of EU programmes can be designed and how well the EU can monitor and exercise control over them. Large EU borrowing to provide unconditional grants to countries appears unconceivable politically and would put the EU on a dangerous and unsustainable path towards more and badly-done integration.

Should one prefer EU control over spending or rely on oversight by the intergovernmental European Stability Mechanism (ESM)?

The EU mechanisms of the multiannual financial framework and new EU instruments have several advantages. Building on the experience of the SURE initiative (support for workers and companies), significant joint borrowing by the EU, backed by a guarantee from member states and managed by the European Commission, could be used to raise funds that could be handed to member states in a similar way to EU budget funds, but that would fulfil clearly defined goals and would be monitored and controlled by the Commission. The advantages of this approach are clear:

- First, the EU budget has a strong legal base and a history that provides it with credibility;

- Second, decision-making involves the European Parliament, adding European-level democratic legitimacy;

- Third, the EU has institutions for monitoring and controlling spending, such as the European Court of Auditors and the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF). And while not all spending is done in the right way, well-defined audit processes ensure at least a minimum level of control.

The EU budget also acts as an insurance mechanism for EU countries. Countries that experience strong negative shocks to GDP end up paying less into the EU budget, while they should receive more funds from it. For instance, if Italy’s GDP falls more than other countries, Italy could shift from net payer to net recipient in the next EU budget cycle. In the 2014-2020 cycle, Italy contributed 0.23% of its GDP per year to the EU budget. If in the next cycle it were to receive as much as Spain did over 2014-2020 –the equivalent of 0.18% of its GDP – this would be enough to cover the budgetary costs of its additional debt[1].

One problem with the EU budget is that the Commission alone is responsible for its execution, even though in reality almost all of the spending is done by member countries. It would be good to have EU-wide projects under the direct control of the EU, but the Commission is not equipped to manage projects.

Overall, EU-based programmes establish EU-level control, and EU-level legitimacy that comes from the European Parliament and member states through the European Council and the Council of the EU, even though the mechanisms are far from perfect.

This is very different for ESM-based mechanisms, in which legitimacy and accountability are achieved at national level only. In fact, as the debate in the Eurogroup has shown, ESM-based programmes pit national interests against each other. This is unsustainable. Take again the example of Germany. It is unconceivable that the Bavarian prime minister, just because he is from a fiscally and economically strong state, would be allowed to exercise accountability and control over spending in North-Rhine Westphalia. Instead, he would exercise his control rights through the federal institutions of the Bundesrat and Bavarian MPs in the Bundestag.

When it comes to spending, don’t we need more control than just some EU oversight comparable to the oversight over Structural Funds?

When one moves from lending to grants or European spending, the issue of control over spending becomes central. As the size of the programme increases, the issue becomes even more important. If leaders aim for joint borrowing of €1.5 trillion, which would be distributed over two years, EU oversight would need to go beyond the current regime of oversight for Structural Funds, in order to be politically acceptable.

One idea is to use EU-borrowed funds to fund EU programmes[2] – in effect to really have European spending. To work, this option requires greater EU-level capacity to define and monitor spending. Pure grants without any European-level definition of the type of spending would be politically difficult.

At the very least, moral-hazard considerations related to such catastrophe insurance require control over spending during the programmes. But moral-hazard concerns go beyond specific spending as the value of insurance is greater for those that have less domestic fiscal space. This moral hazard concern could be addressed by establishing EU control over spending also in good times beyond the pandemic. In that scenario, true insurance could be provided by delivering more funds to countries that are particularly in need, than actually raised from that country via taxes. However, experience suggests that such control cannot be achieved as for example the Fiscal Compact is not really applied (and for good reasons). Alternatively, the pay-outs from the joint borrowing could be distributed to all countries according to the size of the exogenous shock (for example the severity of the pandemic) or even capital keys – ie unrelated to prior debt accumulation.

Is EU debt allowed under the Treaties?

We have argued that Article 122 (2), which deals with assistance to countries in exceptional circumstances, would allow for some joint borrowing to support some member states. But whether this basis would be enough to roll out a union-wide major borrowing initiative of €1.5 trillion is a question only lawyers and judges can answer. The beauty of using Article 122 (2) is that it would clearly become a one-off facility to deal with the pandemic. It might therefore be politically more easily acceptable than a mechanism that would create a permanent fiscal union. Nevertheless, using this mechanism would show that in times of need, the members of the EU stand together and provide collective insurance. This would be an important precedent for all future major shocks. Catastrophe insurance is the most important insurance and the EU would provide it. Unfortunately, Art 122 (2) would not directly involve the European Parliament in the decision making.

And what about the European Central Bank: can it cancel debt?

The interplay between monetary and fiscal authorities is of fundamental importance to deal with a shock of the size triggered by the pandemic. The ECB took the right decision to increase its bond purchase programme with PEPP (the pandemic emergency purchase programme). By increasing liquidity in sovereign bond markets, this alleviates the burden on fiscal authorities of additional debt.

ECB bond purchases do not mean a monetisation of debt. ‘Monetisation’ is in fact a rather blurred concept with many shades of grey. The EU Treaties prohibit monetary financing, which is defined in Article 123 as overdraft facilities to governments or EU institutions, and bond purchases in primary bond markets. The ECB can go further with its bond purchase programme in secondary markets without reaching the limits of the treaty and its current jurisdiction. But clearly there are legal and political limits, as shown by rulings of the Court of Justice of the EU and the German constitutional court.

These legal and also political limits would likely be less binding if the ECB bought EU debt instead of national debt in secondary bond markets. Put simply, the legal limits on national bond purchases relate to the fear that large buying of national debt in secondary bond markets would, de facto, be the same as purchases in primary bond markets, thus violating Article 123 of the Treaties.

Should we worry that large ECB bond purchases lead to too much inflation?

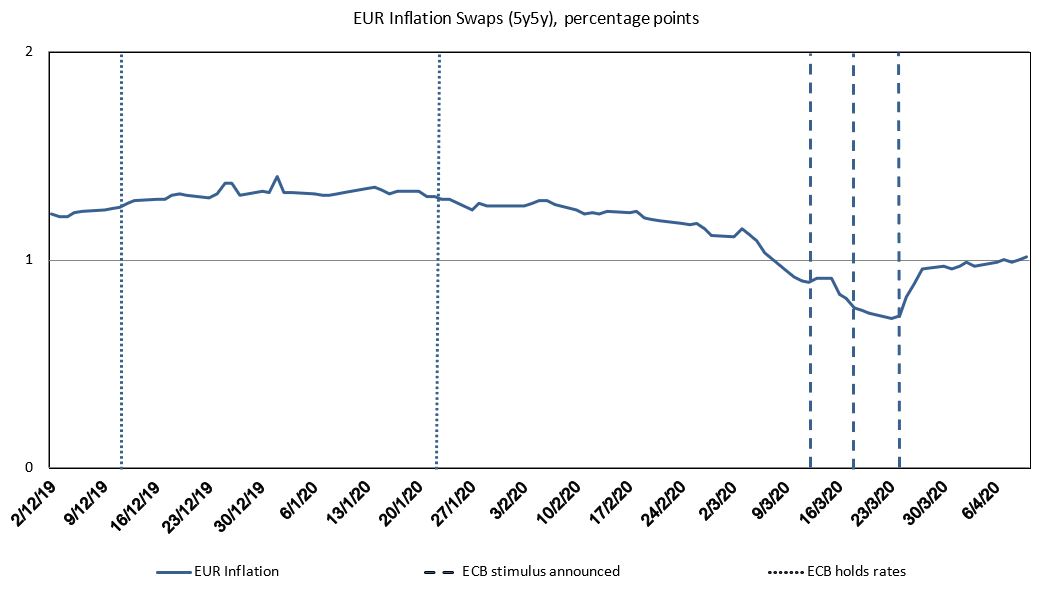

So far, the pandemic has been deflationary (see chart). Moreover, ECB holdings of sovereign debt represent 18.5% of euro-area GDP, less than half of the ECB’s balance sheet. There is thus ample scope to control any inflationary pressures in the unlikely case that they arise in the future. If anything, policymakers should worry about too little inflation at this stage.

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg. Notes: On the 12th of March the ECB left key rates unchanged but announced a comprehensive package of monetary policy measures. On the 18th of March the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) was announced. On the 24th of March the Decision (EU) 2020/440 of the European Central Bank on the PEPP was published.

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg. Notes: On the 12th of March the ECB left key rates unchanged but announced a comprehensive package of monetary policy measures. On the 18th of March the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) was announced. On the 24th of March the Decision (EU) 2020/440 of the European Central Bank on the PEPP was published.

So what is the bottom line?

EU debt to cope with the consequences of this crisis is highly desirable. However, it can only be delivered in a framework in which joint borrowing is not separated from control over spending and revenues. Establishing such control via intergovernmental mechanisms will likely be politically unsustainable for such a health shock. Failing to put in place any control mechanisms would likely be equally unsustainable. The right road is towards some temporary EU debt for the temporary catastrophic shock. Catastrophic shock insurance increases the stability of the system and is therefore in the interest of all members of the system.

Agreeing on a good system will likely require several European Councils as it requires establishing acceptable mechanisms of control, accountability, spending design, and the right legal base. It may very well be that limits of the EU Treaty are too tight and that treaty reform becomes unavoidable or that new treaties outside the EU Treaty need to be established. But for the time being, Art 122(2) offers at least some options. And the fact that institutions such as the Commission, the European Parliament and the European Court of Auditors exist is a good starting point.

During the euro-area crisis, the European Council met on a monthly basis. The magnitude of the current crisis is even greater. It would be wise if leaders agreed on monthly meetings to discuss the way forward. EU leaders should not leave it to the ECB alone to support the system.

[1] To give a concrete example: if Italy’s debt were to increase by 20% of its GDP (as forecast currently by the IMF, 2020), the additional annual interest costs of that debt would amount to 0.3% of Italian GDP, given an interest rate of around 1.5% at the time of writing.

[2] For example, all those who are unemployed for more than six months could receive a percentage of their last salary, say 50%, from the EU. The disbursement would be done through the national authorities but the support would be designed by the EU. Another scheme could consist of support for companies across the EU, with support provided by national authorities but under terms defined by the EU and monitored by DG Competition in the framework of enhanced state-aid control.