Versions of this opinion piece are appearing in Handelsblatt, Le Monde, El Pais, Kathimerini, Rzeczpospolita, Helsinki Sanomat, Caixin, Nikkei Veritas and others.

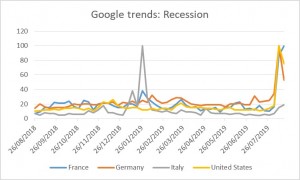

Recession! This is the new worry in Europe and the US. A simple look at google trends shows that in Germany, France and the US, search interest for recession peaked in the last weeks. In Italy, the peak already occurred end of January. Whether a recession is actually occurring is difficult to gauge in real time. But there can be no doubt that significant risks such as the trade war and no-deal Brexit exist.

For European finance ministers, the situation represents a new challenge. When major recessions happened in the past, finance ministers knew that the central bank would be the first line of defence. But with interest rates at zero, room for cutting is very limited for the ECB. Still, the European Central Bank may still push the rate on excess reserves further into negative and restart some sort of asset purchase programme.

All of this ECB action can be somewhat useful, but the reality is that central banks’ ability to control inflation and manage the business cycle may be extremely limited at this stage. The former ECB vice president, Vitor Constancio, recently admitted that it is a “theoretical myth that – in any circumstance – monetary policy alone can control inflation at will”. In the same vain, former US secretary of the treasury and Professor of Economics at Harvard, Larry Summers, argues that structural and fiscal policies are now the key policy tools.

This puts the ball squarely in the camp of European finance ministers. But to succeed, a fundamental change of the finance ministers’ mind-set is needed:

It isn’t enough to rely on automatic stabilisers as Bundesbank President Jens Weidman has just suggested. The problem is that automatic stabilisers kick in late, when workers have already lost their jobs. Automatic stabiliser can only dampen the downturn. Alone, they are insufficient to fend off a recession.

It is time for Europe’s finance ministers to move from reaction to pro-active insurance against downturns. They should prepare concrete spending plans and tax cuts that could be quickly activated should the recession fears materialise. Contingent spending plans should be put in the budget of 2020 already now.

Given the risks to the outlook and the negative real interest rates, some measures should already be put in place to mitigate chronic underinvestment. In fact, recent estimates on the low equilibrium yields suggest that Europe has a weakness in investment and excess savings. Ideally, fiscal policy measures should therefore be targeted at long-standing investment gaps. Two concrete measures come to mind:

First, it would be appropriate for Germany to decide a full depreciation allowance for corporate investments in Germany for a period of say 5 years. This would not only provide an immediate incentive for new corporate investments. It would also tackle a long standing weakness of the German economy: its low rate of corporate investment. Contrary to a corporate tax cut, such as a step would not be a giveaway to companies but a time-limited incentive to invest. And a better capital stock would also help lift salaries.

Second, a significant public investment plan to green the European economy is needed if Europe wants to achieve its goal of climate neutrality. The financing of a sustainable European economy would require very significant investments, hence the name “green new deal”. In fact, relying only on higher prices for carbon is unlikely to be acceptable. Citizens and companies need to see credible alternatives to their existing ways of life and doing business. Only large, publicly supported, investments could fill this gap. It would also provide a boost to Europe and could be funded literally at zero or even negative costs in the zero interest world.

The question is then how to fund such investments in Europe. Relying only on national budgets is likely going to be insufficient. Not only are some countries’ budgets severely constraint. But countries will also tend to rely on European partner countries to do much of the heavy lifting when it comes to developing the infrastructure. Clearly, climate change deserves a European response with European financing. The European Investment Bank would be the right institution at the European-level to issue on a large scale sovereign bonds to fund the necessary investments across Europe in green infrastructure.

Many in Europe and Germany such as the for example German savings banks complain about the low interest rates. But those rates are naturally low because so little is invested and so much is saved. The ECB cannot solve this problem. Europe’s finance ministers can. Time to change mind-set from reactive to proactive fiscal policy. Time to provide fiscal insurance against downturns and fund green investments at zero costs.